MALCOLM HEBRON

I once read a good story – whether real or apocryphal, I do not know – about four artists in the early twentieth century, on a painting expedition in the countryside. All had been trained in the academic school, so they knew how to do proportion and perspective, how to use tone to suggest volume, in short how to paint what they saw in the approved realist manner. But they were interested in the new experiments going around, too – bold, unrealistic uses of colour, expressive distortion, experimental composition.

Then one of them made a proposition: ‘Why don’t we all sit down and paint the same tree? Let’s leave all the originality and experimenting to one side, and just paint what we see, as correctly and accurately as we can.’ Agreeing this was a good idea, they set up their easels and canvases and palettes and set to work. Time passed. Birdsong and brushstrokes. After a while, they showed their efforts to each other. And, as you’ve probably guessed already, each painting was completely different. However academic and traditional they tried to be, the act of painting led each one down a different route.

This is great lesson of drawing from life. There is no ‘correct’ depiction of a tree, no accurate version. There is only the experience of the tree before us – unique, unrepeatable, finding its way, through eye and mind and arm, onto a piece of paper or canvas. If there is a real tree, the thing in itself, the ‘Ding an Sich’ as the philosopher Kant put it, then we cannot see it. It is forever surrounded by a cloud of perception, made up of moods, memories, associations, feelings. No approved procedure can quite keep these things away. (In the studio, it might be different: there one could rely on set formulae to make repeatable, predictable images – it is tempting to dismiss such work as mere illustration, but much work by the Old Masters was made like this.)

Fast forward to 1958, and in a fascinating film, Four Artists Paint One Tree, we can see our possibly mythical story take on real life. In this animated educational film, four Disney illustrators render the same tree, in fascinatingly different ways, and explaining their approach. Each version of the tree is as real and authentic as the next. And each is quite distinct.

We do not see the same tree – or landscape, or stone, or face – as each other. We can’t. We can’t even see the same thing inexactly the same way as we did yesterday. Both I and eye have subtly changed. And the world is constantly changing, too. In the Wayne Wang film Smoke (1995), with screenplay by Paul Auster, the central character is a Brooklyn tobacconist, Auggie (played by Harvey Keitel). Every morning at 8.30 am Auggie steps outside his shop with his camera and takes a picture of the same street corner at the same angle. The photo album of these pictures (these are pre-digital days) is his life’s work. When a friend, mystified, says all the pictures are the same, Auggie explains in a beautiful speech how they are all the same yet different: the people, the cars, the slant of light, the sky – nothing is ever quite repeated. You cannot step into the same river twice. As a guide to the art of looking and seeing, that speech has stayed with me ever since.

Auggie’s photographic practice, and the story of the painters, came into my mind recently. Lockdown, for all its constraints, also helped me to pay more attention to the patch of world immediately around me. In the early evenings, when I was usually at my desk, I found my attention drawn to a line of trees beyond the garden. For years I had been aware of them, but now I was more consciously looking, giving the view my attention. I decided, at the same time each evening, to make some quick drawings of them. This is a well-recognised exercise: Degas advised artists to draw a subject not once, but dozens of times – probably for the same reasons as Auggie takes his photographs. We are always exploring, always discovering. Another healthy result of such an exercise, beyond the training it gives to eye and hand, is that you never think of a particular image as closure, as ‘the product’. Each is simply a stage in an ongoing process, a graphic record of a momentary encounter.

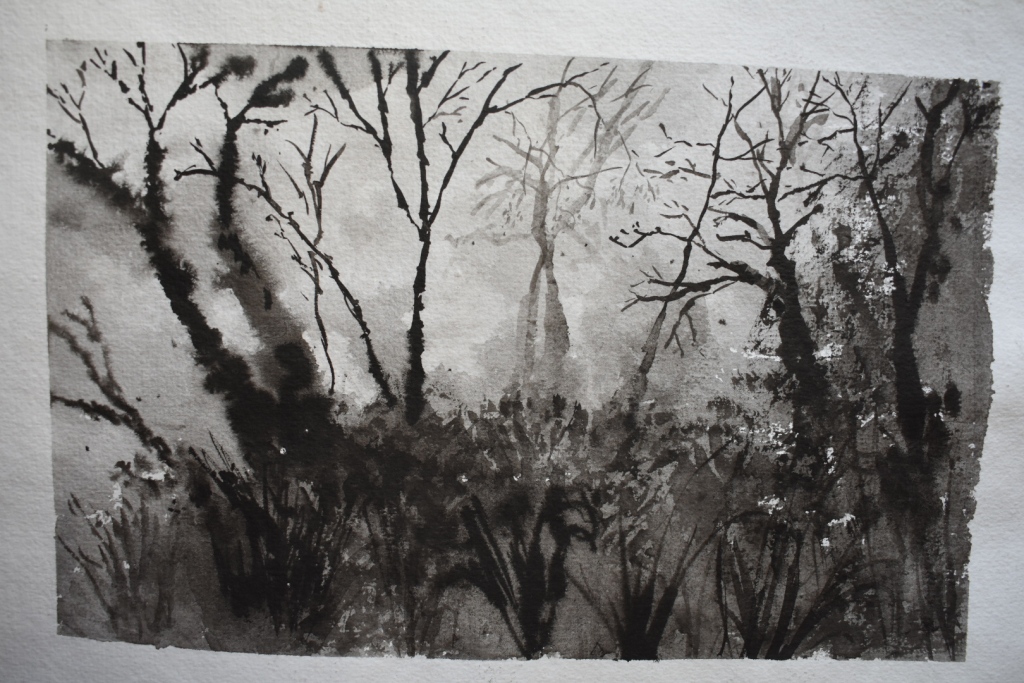

Below is a selection from the series of drawings of ‘Trees at Twilight’. They involve different techniques: drawing ‘blind’, that is, without looking down at the paper at all; using the ‘wrong’ hand (left, in my case); holding the instrument at arm’s length or in an unusual way, to surrender control and get unpredictable effects, and so on. The media change – pencil, charcoal, ink. They are not in a strict sense drawings of the trees at all. Rather, they use the trees as a starting point for the drawing, the activity of making. It is an important distinction, and explains why the task those four travelling painters had set themselves was so elusive: you seek to draw a tree, but the tree draws you. It is entirely and wonderfully unclear what is guiding the hand, hence the feeling of many across the arts that they are in some way mere witnesses to what they produce. I share the drawings here as a record of successive moments of seeing, the traces of irrecoverable encounters, a mark in the evening, a step in the river.

1958: Old Disney artists show their various painting techniques through a nature study.

Malcolm Hebron is an English teacher in the UK and divides his time between the counties of Hampshire and Devon. His academic publications include Key Concepts in Renaissance Literature (Palgrave) and How to Read a Poem (Connell). He edits the journal for the English teaching profession The Use of English, published by the English Association. He is currently translating texts by the medieval Mallorcan philosopher Ramon Llull. His primary interest is in the creative process, explored practically through poetry, photography and art, principally drawing (see Instagram account @hebronmalcolm).

In this article, some experimental art work by the author.

(Edited by Silvia Pio)

For the articles included in The Albero Project, click on the tag.