LESLIE MCBRIDE WILE

Somewhere a bell was ringing—an old bell, a school or a church bell, swinging slow and heavy. Joanne surfaced, up from sleep into the sonorous pealing, felt the darkness of early morning on her eyelids. She sensed her cheek and the pillow where it rested, her left shoulder sunk into the too-soft mattress, the weight of the Hudson Bay blanket covering her. The narrow bed was warm and she stretched, rolling onto her back, flexing toes and fingers. Thoughts formed, the world beyond bed spun into focus. She remembered where she was, and why. Gripping the top edge of the heavy blanket, she tossed it back and sat up, groping with her feet for the moccasins she’d brought from home. She took a shabby cardigan from the back of John’s desk chair, slipped it over her pajamas, shuffled to the door and into the narrow hallway to the bathroom.

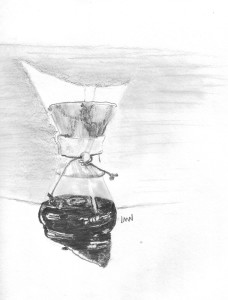

In the kitchen Joanne put the kettle over a high flame and fitted a cone-shaped paper filter into the mouth of the old Chemex coffee maker, spooned oily black grounds from a yellow Bustelo can and put it back into the refrigerator. John still drank coffee, and so did she. The kettle boiled. Joanne poured water over the coffee in the paper cone, carefully, carefully. A thin stream of coffee ran from the tip of the filter into the bottom of the glass pot, and slowly she poured the rest of the water over the grounds, almost filling the cone. Joanne stood with the empty kettle still in hand, looked without seeing at harsh light reflected on blank, black window panes, into the shadowless dark beyond the kitchen.

She heard the door to John and Martha’s bedroom open, then softly close again. The bathroom door closed, water pipes groaned briefly, and then she heard the shower curtain scraping across the rod, metal on metal. She removed the paper cone from the Chemex, gathering the edges neatly in her left hand, her right hand cupped underneath to catch drips. Stepping gently on the pedal-operated trash can she dropped the filter, rinsed her fingers at the sink, dried them on a small linen towel, white with red stripes. Joanne put two slices of brown bread into the toaster, set a small round table with two plates, two paper napkins, two spoons and two knives. She took butter, jam, and milk from the refrigerator and a bag of granola cereal from a cupboard. She took down two bowls and set them beside the cereal.

She ran fresh water into the kettle, placed it back on the burner, lit the gas again, low this time. She took a cobalt blue teapot from a cupboard, dropped a sachet from the Chinese pharmacy into the pot. It smelled like dust and something sharply unpleasant, but they were trying everything they could think of. The phalanx of bottles filled with pills, capsules, and powders, massed in the center of the table, were only one of the armies they raised to fight for Martha’s life. They went to Chinatown for herbal remedies, to a naturopath for a special diet, to a physiotherapist for help with the pain, to the neighborhood dealer for hashish, which Joanne mashed with honey. A spoonful helped to quell Martha’s nausea and vomiting after a bout of chemo.

Joanne heard footsteps, slow and heavy on the creaking boards of the hallway floor.

“Hi, Mom.” She turned to him, trying for a smile. John stood in the doorway, his big shadow falling behind him into the hall. His hair was still wet, black and spiky, thick and coarse like hers, and his freshly shaved cheeks showed faintly blue. In black corduroys, white shirt and tie, he was dressed for work. Joanne saw her elder son, a tall man, a stubborn small boy, worried, determined, brave, frightened. She smiled at him then.

“Morning, John. How was last night?”

“Not too bad. No sweats anyway, and she only woke up a couple of times that I know about. Is there coffee?”

Joanne lifted the Chemex by the weathered wooden saddle around its waist, poured coffee into a tall white mug for John, into a low white cup on a saucer for herself. “Is she awake?”

“She was sleeping when I got up.” John took his coffee, sat at the table. “Just toast, Mom, okay?”

Joanne took a plate from the table and placed it beside the toaster, pressed down on the bar, watched the bread drop into the slots. The kettle boiled again. Joanne turned off the gas, poured water over the sachet in the teapot. She sat across from her son, spooned sugar into her cup and stirred, the sound of metal against porcelain like a ringing in the ears. The toast popped up. John said, “I’ll get it.” Joanne looked up, still stirring her coffee. The window showed grey light, the reflected glare softer now, and the corner of a wall, red bricks patched with concrete, a lighted window across the air shaft.

John stood at the kitchen door again, armored against February in a sheepskin jacket, leather gloves, no hat. “I’ll call around noon, Mom, see how it’s going. Bye.”

“Have a good day, John.”

Joanne cleared their breakfast dishes and took a folding tray from its place between the refrigerator and the sink. She placed it on the table, wiped it, set it with the cobalt blue teapot, a matching cup, a napkin, a spoon. She washed a grapefruit, dried it carefully, placed a scarred wooden cutting board on the countertop to slice the fruit the way Martha liked it: top and bottom off, fruit halved lengthwise and then crosswise, each quarter cut into thirds. Joanne scooped up the pieces and placed them in a shallow white bowl with a blue fish painted in the bottom. The scent was bright and fresh, the fruit cold and juicy, yellow rind and ruby flesh. Her hands were cold and she rinsed them again, in warm water at the sink.

Joanne walked down the short hall to the bedroom, knocked, opened the door slowly. Martha lay propped against white pillows, under a cobalt blue bed cover. John had helped her to the bathroom and back again; her hair was combed and she wore fresh pajamas. “Hi, Joanne. It sure looks cold out there. I’m glad I don’t have to go out this morning!” The shadow of a grin flickered, then she turned her face toward the window. Pale winter sun was breaking across uncounted city rooftops, steam venting from chimney pipes, pigeons fidgeting on a fire escape.

“Me too.” Joanne smiled then. “Do you want some tea?”

Martha looked back to Joanne, standing in the doorway. “Love some,” she pulled a grimace. “I could eat some grapefruit too.” Their eyes caught, held. Martha looked down at her hands, folded on the cobalt blue bed cover. “I’m glad you’re here, Joanne. Thank you.”

“I’m glad you wanted me. I’d rather be here than back at home, feeling helpless.” Joanne wrapped the big cardigan tighter around her, crossed her arms, slid her left hand up to her right shoulder and down again, gripped her elbow. “I’ll get your tray. It’s all ready. How about a piece of toast?”

“Not yet, thanks. Just grapefruit.”

Joanne settled Martha with her breakfast tray and went back to the kitchen to get another cup of coffee, the one she usually laced with her first bourbon of the day. She stood still in the doorway, arms across her chest, wrapped in her son’s baggy sweater. She looked at the coffee pot, the dishes in the sink, the floor. Later she would sweep the floor, she decided.

When Joanne was at home, the morning hours were her writing time; the first shot of bourbon in her second cup of coffee, after Howard left for the office, gave her just the inspiration she needed. Some days she worked on a new story; some days she opened the latest returned manuscript, filed the rejection letter, addressed a fresh manila envelope and sent the story on to the next publisher on her long list. She began by sending each new story to The New Yorker, then to The Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s Weekly, and on down the line to all the little magazines published on college campuses or by small presses from New York to San Francisco. Joanne’s stories had been published in some of the little mags, mostly the ones that paid in free copies of their publication.

She managed her drinking as methodically and efficiently as she organized her writing. The first drink would take her to mid-morning, when Lillie Mae arrived. Joanne would brew a fresh pot of coffee and down a second tot while the housekeeper made up the bedroom and gathered laundry. By midday Joanne finished working at her desk. On the days when she had no meeting to attend, no luncheon date, she ate a light lunch and then turned to gardening, reading, or some household project. Joanne took an ounce of bourbon after lunch and another at mid-afternoon. In summer she might swim in the backyard pool after Lillie Mae left at 4:00. Then Joanne would shower and change clothes, start dinner preparations. Howard returned by 6:00, to find her in the kitchen sipping at a double bourbon, the dining table set, the house immaculate, his wife relaxed and happy.

Martha’s diagnosis had disrupted Joanne’s measured life, her precisely calibrated days. At odds with her own mother, Martha asked Joanne to come and stay, to help her through the ordeal of chemotherapy and whatever else might lie ahead. The cancer was aggressive but Martha was just 32, young and strong. Maybe, Joanne thought, if she did this thing, if she gave up her painstakingly maintained, bourbon-tempered life, maybe this story could have a happy ending.

Joanne breathed, dropped her arms, shuddered. She smelled bourbon, tasted it with her mind. She poured coffee into her cup and added sugar. She balanced a spoon carefully on the rim of the saucer, carried the saucer, cup, and spoon down the hall to Martha’s bedroom. Martha was dozing, the breakfast tray still before her. Joanne set her cup on a bedside stand, lifted the tray from Martha’s bed, set it on the floor near the bedroom door. Bits of herb and twig floated at the bottom of the teacup, the dregs of the Chinese medicine. Martha had managed half of the grapefruit pieces, the skins arranged neatly around the saucer. Joanne curled herself into a worn leather chair beside the bed. She took up her saucer and began to stir the coffee, metal against porcelain like a ringing in the ears. One day she would write about this, she thought. Then she thought, I can never write about this, and knew what was true.

(illustration by the author)