Julia Bridget Hayes, between iconography and photography

You are from South Africa, Nelson Mandela’s homeland, and the land of fight against racial discrimination. In this environment, how did your religious and artistic calling start?

Firstly, thank you for inviting me to be interviewed. I was raised in a family that fought against apartheid in South Africa. My father was an Anglican priest who was banned as an enemy of the state by the apartheid government. My family converted to the Orthodox Church when I was a child in 1987. I had always enjoyed drawing as a child and started seriously trying to draw when I was about 14 years old. I was basically self-taught because a teacher had discouraged me from taking art classes at school, telling me, “What will you do with art?”… I had always had a dream of becoming a photographer and when I finished high school I studied photography at the Pretoria Technikon (now Tshwane University of Technology), but for financial reasons I had to stop my studies during my second year. At that time I started soul searching and reading up about the Orthodox faith and had the crazy idea that I would like to study theology, but there was nowhere in South Africa that I could study Orthodox theology, so I gave up on the idea.

How did you approach iconography?

It would probably be better to say that iconography approached me! I had never even considered iconography, but after leaving the photography school I spent every spare moment I had painting. After about a year I had reached rock bottom and didn’t know what to do with my life. In my despair I asked God why I could paint, why it was the thing I do best and what I was meant to do with it. And that is where the adventure began! Just two days later a priest saw something I had drawn and said he’d send me to Greece for 6 months to learn iconography! I had waited for nearly a year, when he told me that he was sending me to university, that I had one night to decide what I was going to study and that he hoped I’d sleep well! Needless to say, I didn’t sleep a wink. The only thing I had ever contemplated studying at University was theology. And in 1997 my impossible dream came true and I came to Greece to study at the Department of Social Theology at the University of Athens.

Due to the pressure of my studies I didn’t have the time to dedicate to learning iconography. I did attend a few lessons at a parish, but they didn’t even teach the basics of sketching. We were just shown the technique for painting an icon in the Cretan style, so I took what I could from there and worked on it myself with the help of books. I also later experimented with the Macedonian style. But I had never really been satisfied with the idea of simply making “photocopies” of old icons.

Due to the pressure of my studies I didn’t have the time to dedicate to learning iconography. I did attend a few lessons at a parish, but they didn’t even teach the basics of sketching. We were just shown the technique for painting an icon in the Cretan style, so I took what I could from there and worked on it myself with the help of books. I also later experimented with the Macedonian style. But I had never really been satisfied with the idea of simply making “photocopies” of old icons.

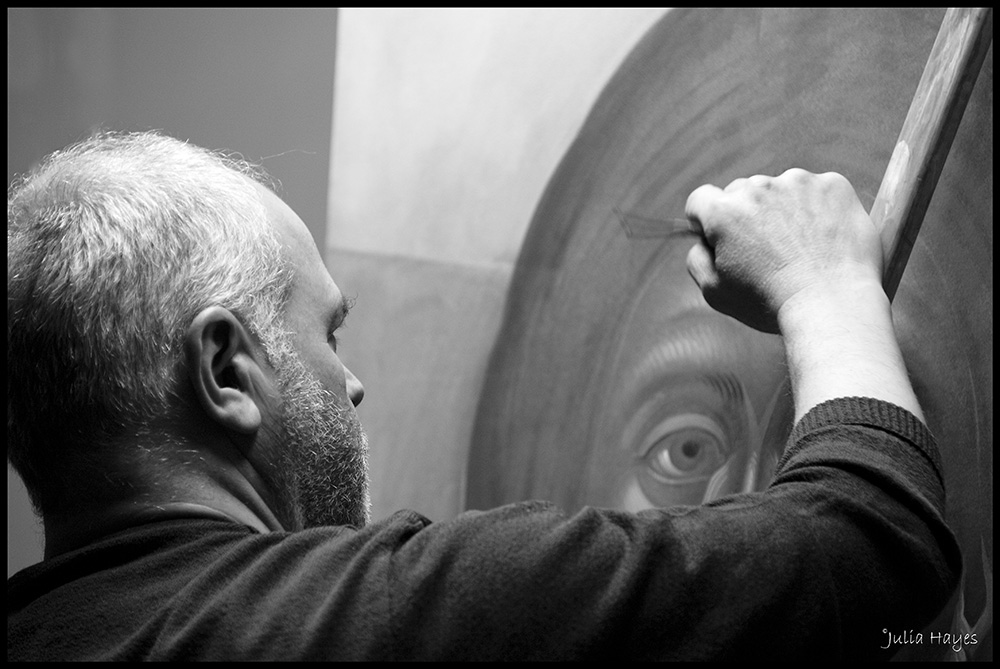

It was only in 2008 when I was doing my postgraduate studies that I started attending George Kordis’ classes at the Theology Faculty of the University of Athens – both his practical and his theoretical classes in the Theology and Aesthetics of the Icon. He also generously invited me to attend classes at the Centre of Orthodox Icon Painting Studies and Research Eikonourgia, where we were taught by a team of qualified and talented iconographers, led by Kordis himself.

How do you manage to match tradition and innovation in your iconographic art?

The idea that the tradition of iconography is to make exact copies of old icons only appeared in the 20th century. Throughout the history of Byzantine iconography there was a continual creative development of certain aspects of painting, while others remained unchanged. What is essential to the icon and cannot change is the external form of the person. This is the very definition of the icon according to the Church Fathers and Councils. This is why an icon of St Peter from the catacombs and one painted in the 21st century are immediately recognizable as the person of St Peter. How that form is depicted in terms of painting technique and style is up to the iconographer. The style of painting may differ from one period to another as can clearly be seen in the differences in styles between the Comnenian, Paleologian and Cretan schools. You may ask, why then paint in the byzantine manner and not a naturalistic style? There is a very important reason we paint in the byzantine manner and why the Orthodox Church preserves this traditional manner of painting and it has to do with the liturgical and ecclesiastical function of the icon.

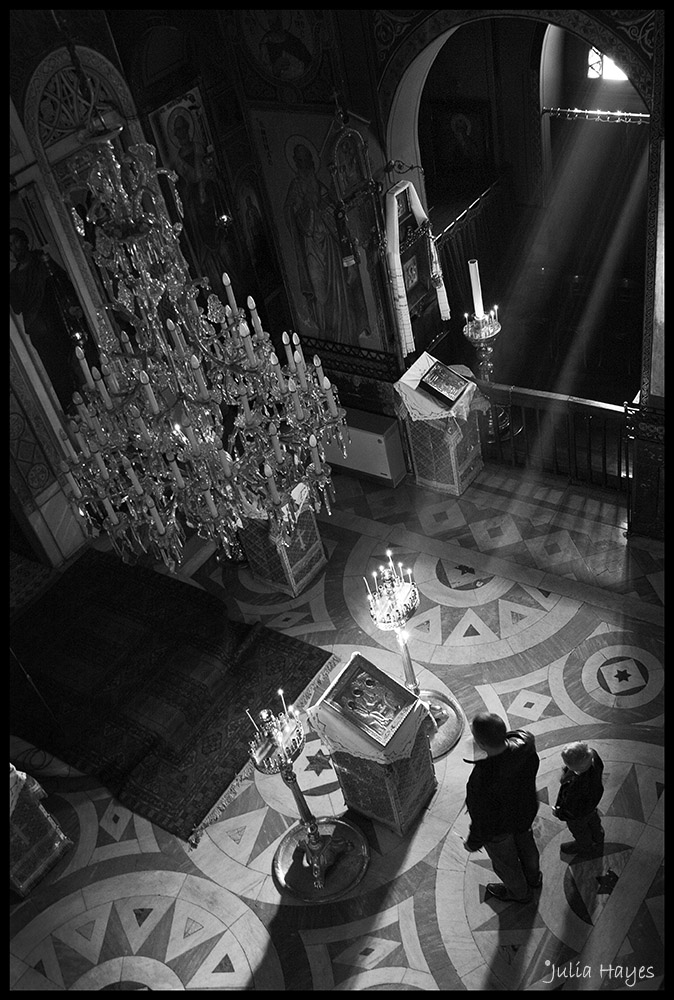

Unlike the Western understanding of the image as a medium that conveys meanings, ideas, feelings etc, the Byzantines understood the image as a thing in itself that exists because the person depicted exists (be it Christ or the saints), and it’s purpose is to make that person present in the same time and space as the viewer and to bring them into a relationship and communion with the viewer. Just as the design of an Orthodox Church with Christ Pantokrator in the dome emphasizes the fact that “God is with us” and the icons of the saints on the walls remind us that we are “surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses” (Heb 12:1) and that they are actually present with us. This is achieved with the use of line, colour and rhythm and the fact that the icon has no background so the image is built from the surface, out towards the viewer. If an icon is properly painted it “comes alive” and no matter where you stand the icon will look at you. Once an iconographer knows how to use these tools he is able to be creative within tradition. That is one of the things I try to achieve in my iconography and why every icon I paint is unique.

From your websites we understand that you are also a photographer.

What is photography to you?

I guess my dream of being a photographer has never died! For me, it is a creative outlet and a means of capturing the world and particularly people around me.

“Margutte” deals mainly with literature and art. What readingswould you suggest our visitors in order to understand the art of icons?

I highly recommend the book by George Kordis, “Icon as Communion: The Ideals and Compositional Principles of Icon Painting” which is an excellent starting point for understanding the Byzantine system of painting. The book by Aidan Hart, “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” is probably the most comprehensive book on icon painting techniques available.

With regards to the theology of the icon, I recommend that anyone interested should start by reading the works by Church Fathers who defined and defended the icons such, as St John of Damascus and St Theodore the Studite, before trying to read modern authors whose philosophical influences have distorted the patristic theology of the icon.

(Bio)

Julia Bridget Hayes was born in South Africa and is currently living in Athens, Greece. She is an iconographer, translator, photographer, EFL teacher and writer; a Jack of all trades with a Masters degree in Liturgical Theology from the Department of Social Theology of the University of Athens and is currently working on her PhD about “Liturgical Time and the Icon”. Her hand-painted icons are in churches and private collections in Greece, South Africa, Russia, UK, Ukraine, Finland, Belgium, USA, Indonesia and Argentina and have also been published in the Eastern/ Greek Orthodox Bible (NT). She translates Orthodox spiritual and theological books, articles and websites from Greek into English.