SILVIA PIO

Aladdin, Ali Baba, Shahrazad and Sindbad the Sailor are part of Western collective imagination and have almost become part of our folklore. We all know where they come from: The Thousand and One Nights, also called The Arabian Nights (in Arabic: ألفليلةوليلة, Alf layla wa layla; in Persian: هزار و یک شب, Hezār-o yek šab), a collection of Middle Eastern and Indian stories of uncertain date and authorship.

The frame of the stories is also well known: in Central Asia or “the islands or peninsulae of India and China,” King Shahryar, after discovering that during his absences his wife has betrayed him, kills her and those with whom she was unfaithful to him. Then, hating all womankind, he takes a new bride every day and kills her the next morning, until no more candidates can be found. His vizier’s elder daughter, Shahrazad, devises a scheme to save herself and others and insists that her father gives her in marriage to the king. Each evening she tells a story, leaving it incomplete and promising to finish it the following night. The telling of stories goes on for a thousand and one nights; they are so entertaining that the king is very eager to hear the end and puts off her execution from day to day, until he is finally convinced of Shahrazad’s fidelity.

The first known reference to the Nights is a 9th-century fragment, mentioned in 947 by al-Masʿūdī, historian and traveller, known as the “Herodotus of the Arabs.” But the work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folklore and literature. Many were originally folk stories while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān (A Thousand Tales), dated in 6th–7th centuries, which in turn relied partly on Indian elements.

The expressions “A Thousand Tales” and “A Thousand and One…” were intended merely to indicate a large number and were taken literally only later, when stories were added to make up the number. The collection is often known in English as The Arabian Nights, from the first English language edition (1706) from Galland’s version (see below), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment.

Several layers in the work, including one originating in Baghdad and one larger and later written in Egypt, were distinguished in 1887 by August Müller. By the mid-20th century, six successive forms had been identified: two8th-century Arabic translations of the Persian Hazār afsāna, called Alf khurafah and Alf laylah; a 9th-century version based on Alf laylah but including other stories; the10th-century work by al-Jahshiyārī; a12th-century collection, including Egyptian tales; and the final version, extending to the 16th century and consisting of the earlier material with the addition of stories of the Islamic Counter-Crusades and tales brought to the Middle East by the Mongols. Most of the tales best known in the West, primarily those of Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sindbad, were much later additions to the original corpus.

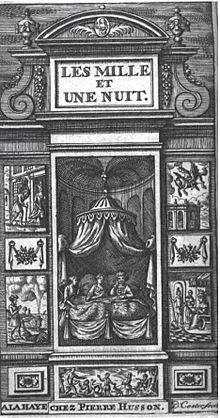

The first European translation of the Nights, which was also the first published edition, was made by AntoineGalland (1646-1715) as Les Mille et Une Nuits, contes arabes traduits en français, 12 vol. (vol.1–10, 1704–‘12; vol. 11 and 12, 1717). The French translation derived from an Arabic text of the Syrian revision of the medieval work, as well as stories from oral and other sources, based on a manuscript in three or four volumes from the 14th or 15th century. Three volumes of that manuscript are stored in the National Library of France in Paris. Galland’s translation altered the style, tone and content of the Arabic text. Designed to appeal, it omitted sophisticated or dark elements, enhanced exotic and magical elements and became the basis of most children’s versions of The One Thousand and One Nights .His translation remained standard until the mid 19th century, with parts even being retranslated into Arabic.

The Arabic text was first published in full at Calcutta by the British East India Company (1814, and later 4vol.1839–‘42). The source for most later translations, however, was the so-called Vulgate text, an Egyptian revision published at Bulaq, Cairo, in 1835,and reprinted several times.

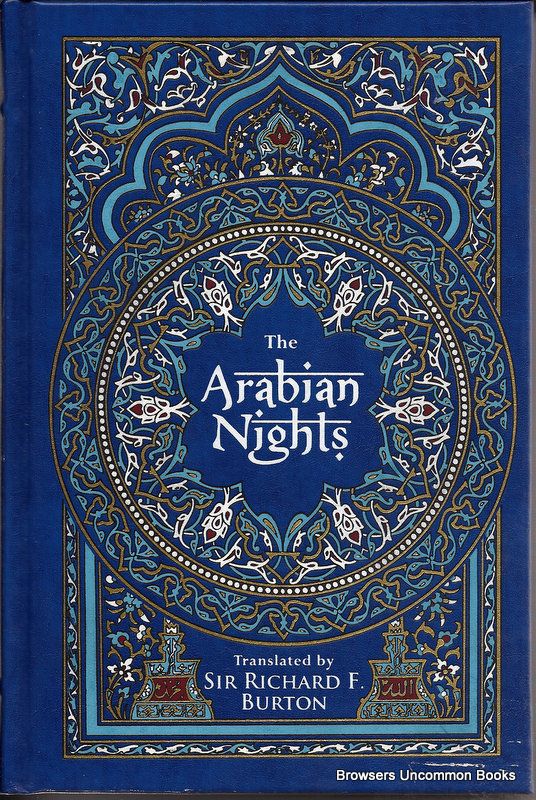

Meanwhile, French and English continuations, versions, or editions of Galland had added stories from oral and manuscript sources, collected, with others, in the Breslau edition, 5 vol. (1825–43) by Maximilian Habicht. Later translations followed the Bulaq text with varying fullness and accuracy. Among the best-known of the 19th-century translations into English is that of Sir Richard Burton, British explorer and Arabist, who used John Payne’s little-known full English translation The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night to produce his The Thousand Nights and a Night[1], 16 vol. (10 vol., 1885; 6 supplementary vol.,1886–88). Payne’s and Burton’s were the two unabridged and unexpurgated English translations done in the 1880s[2].

Burton made a special study of the sexual imagery in the source texts (adding extensive footnotes and appendices on “Oriental” sexual mores); therefore, due to the strict Victorian laws on obscene material, both translations were printed as private editions for subscribers only. Burton’s 16 volumes hada huge public success and many prominent admirers but were also criticised for their archaic language and extravagant idiom, and obsessive focus on sexuality; they have even been considered as a highly personal reworking of the text.

Many other translations appeared in French, English, German, Italian, Russian, Spanish, mainly based on Galland’s translation. In the 20th century translations into Chinese, Japanese and Hebrew were also produced.

At the end of the 20th century Muhsin Mahdi (1926–2007), an Iraqi-American islamologist and a abist and a leading authority on Arabian history, philology, and philosophy, wrote the first critical edition of The One Thousand and One Nights, based on the earliest still existing manuscripts, originally published in three volumes (1984-1994) and reprinted many times. Many other versions are based on his work, including the Italian translation by Roberta Denaro and Mario Casari, recently published by the Italian publisher Donzelli, from which the illustrations for this article are taken, beautifully done by Cinzia Ghigliano of Mondovì.

The thousand and one versions and translations of this work, the arguments about the authenticity and the origins of the sources, leave intact the fascination of these stories, that for more than a thousand and one years have been entertaining listeners and readers, especially those in the West who for three hundred years have been following Sherazad’s tales through works (and now I am quoting one of the first translators in English, John Payne[3]) which have transplanted into European gardens the magic flower of Oriental imagination.

(Drawings by Cinzia Ghigliano)

[1]The works stood as the only complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) of the “Arabian Nights” until the Malcolm C. and Ursula Lyons translation in 2008.

[2]Burton’s ten volume version was published almost immediately afterPayne’s. with a slightly different title. This led later to charges of plagiarism.

[3] John Payne, The Book of the Thousand and One Night: its History and Character, 1884, http://www.wilbourhall.org/pdfs/thousandandonenights/payne/bookthousandnig00payngoog.pdf, the quotation refers to Galland’s work, of which Payne writes a detailed critique.

Some of the sources:

http://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/culture-magazines/arabian-nights-frame-tale

https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Thousand-and-One-Nights

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Thousand_and_One_Nights

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_mille_e_una_notte

http://www.wilbourhall.org/pdfs/thousandandonenights/payne/bookthousandnig00payngoog.pdf